Blonde Roots (2009)

Why this one?

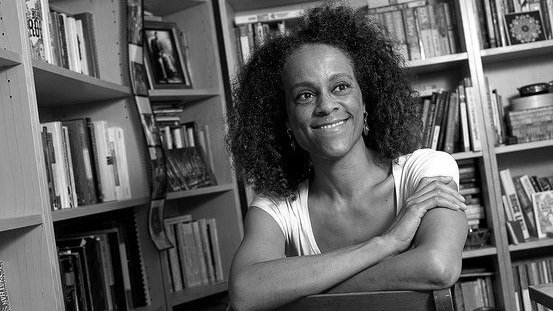

Like many others, I very much enjoyed Bernardine Evaristo’s 2019 Booker Prize winner, Girl, Woman, Other. I was definitely keen to read something else by her, and the premise of this one sounded particularly unique and intriguing.

Blonde Roots came many years into Evaristo’s writing career but was nonetheless her first straightforward “novel in prose”, following previous works that incorporated significant poetic elements.

Thoughts, etc.

Blonde Roots has a concept that’s hugely appealing in its simplicity: it imagines a world in which the history of the slave trade is inverted, where “blak Aphrikans” are the masters and “whyte Europanes” the enslaved. Its central character is Doris Scagglethorpe, a white Englishwoman who is kidnapped as a child and taken on a slave ship to the New World (in the "West Japanese" islands) where she is acquired by the plantation owner Bwana, also known as Chief Kaga Konata Katamba I. She is ultimately moved to the imperial capital of Londolo, in the island of Great Ambossa where she becomes a "house slave" until her attempt to escape. As punishment, she is returned to the plantation and ends up labouring in the fields, suffering incredible hardship and dreaming of a final escape.

There's no doubt that the setup is hugely intriguing. Some aspects of history are straightforwardly flipped, but there are further degrees of complexity layered in - while the England Doris comes from is agricultural, redolent of an era even before the peak of the real historical slave trade, the imperial heart of Great Ambossa feels more like a dystopian future, with its capital Londolo featuring the ruins of an Underground rail system (something Evaristo has a lot of fun with in flipping the names of London Underground stations to sound more "Aphrikan.") This lends the novel a slightly science-fictiony flavour that isn't perhaps what you'd expect from the premise.

Despite this, large sections of the novel are faithfully rendered and familiar from historical accounts. The description of the horrific conditions on board the slave ship makes for hard reading, as does the graphic rendering of Doris' punishment following her escape attempt. Having relatively recently read Sacred Hunger as part of my Booker project, it was refreshing to read a description of these dark experiences from the perspective of those who suffered, rather than the slave masters as in Unsworth's otherwise excellent work.

There's a virtuoso section in the middle in which Bwana mounts a defence of slavery in ludicrous over the top language, but with every single inversion rooted very firmly in the reality of what his upper class British Imperial equivalents would have said. It feels wrong to be entertained to the point of laughing out loud when the subject matter is this horrific, but Evaristo manages it with style - largely because it's Swiftian satirical writing at its absolute finest, using the tricks of comedy to expose the utter absurdity of a plethora of self-justifying Imperialist arguments - which make just as little sense whichever way you flip them - proving that language can be twisted in the service of evil, no matter who is doing the writing.

Elsewhere, the impact of the inverted history is patchier. At first intriguing, it does on occasion seem like Evaristo is having that little bit too much fun with the linguistic games and name-flips at the expense of making and grander points. The power in those first-person accounts of horrors isn't necessarily altered one way or the other by the inversions - you don't (I would hope) read them going "isn't this horrific because she's white" and the focus in your mind can't shift that far away from the fact that those who suffered historically were quite evidently black. Towards the end of the novel, in the plantation where the "Europanes" are given Aphrikan names and fully immersed in the world, it becomes increasingly difficult to remember that they were supposed to be "whyte" in the first place. All of which renders the point of the switch a little obscure - just a neat trick to get you "through the door" and then essentially read a very good novel about the realities of slavery? I guess it worked in my case, so maybe no bad thing? I suppose ultimately it's there to give fresh perspective to a well written about subject - and when it works at its best (as in Bwana's "defence of slavery" section) it works brilliantly. And elsewhere, it's still... a very good novel about the realities of slavery.

Score

8

Definitely still a really interesting and thought-provoking read, but not quite up there (for me) with Girl, Woman, Other.

Next up

Next on the Women’s Prize winners read-through is Carol Shield’s 1998 winner, Larry’s Party.